THE UNHOMELY PROTOTYPE: 'THE 'SERAGLIO' AND THE UNSETTLING OF AMINA' PRESENTS:

Amina & Huda

A DOUBLE PERFORMANCE

أمينة وهدى

'Amina & Huda' is a film and script of three acts, in which Amina, the protagonist of Naguib Mahfouz’s Palace Walk who experiences extreme purdah at the hands of his tyrannical husband, Al-Sayyid Ahmad and consequently ‘does not know much of the outside world, is confronted by uncanny visions of a biographical figure, Huda Sha’arawi (1879-1924) from her memoirs, Harem Years, an outspoken feminist who existed in Amina’s time but not of her world, who advocated for the liberation of the woman from the harem system and both the patriarchal gaze and rule depicted in both Huda's memoirs and Mahfouz's Palace Walk. The film introduces these ‘visions’ by employing uncanny filmic and literature tactics (The Double, Imaginary and Recurring Manifestations, etc.) informed by the theoretical framework of Sigmund Freud’s Uncanny (1990) and Anthony Vidler’s 'The Architectural Uncanny' (1992) in the home place.

The Unhomely Prototype explores if Amina could realize these illusions doubled/layered onto her own ‘spaces of refuge’ to not only unsettle her visually, but to unsettle her with the prospect of physical and social liberation. In doing so, the project explored how and where these ‘utopias’ are created in Palace Walk but also proposes an exhibitive rendition of the co-existence of both narratives, Amina’s and Huda’s. The Prototype employs Michel Foucault’s third heterotopic principle; that of the theatre or cinema as a site that “juxtaposes several spaces that would normally be incompatible” and “unfolds a whole succession of anomalous places on the rectangle of

the stage…” (Foucault et al., 2014, p.21).

PROPOSAL

THE UNHOMELY PROTOTYPE

In what method or medium can ‘uncanny similarities’ in different realms of text (i.e Palace Walk and Harem Years) that concern the female embodiment of space and refuge, and of feminism be successfully interpreted using interpretive spatial/classical means of the unhomely/the haunting/the ghostly? And could such representations challenge how lived experiences are created as an archive of the homespace? Equally as important, what medium could successfully capture how Huda (Harem Years) and Amina (Palace Walk) are forced to occupy the harem system home space in multiple heterotopic ways? That is how do they conform, resist, and find refuge in patriarchal domestic spaces that configure their spatial understanding and navigation?

Prompted by Michel Foucault’s third heterotopic principle of the theatre as a site of anomalous, multiple spaces and sites occurring in the ‘same’ rectangle of a stage, Vidler and Freud’s positioning of the uncanny primarily a domestic, interior borne phenomenon, and as been portrayed by filmic devices concerning the supernatural and eerie, the Unhomely Prototype proposes:

To exploit architectural forms such as the home space as an archive of lived, controlled, and gendered experiences, in both Naguib Mahfouz’s fictional 'Palace Walk/Bayn al-Qasaryn' and Huda Sha'arawi's biographical 'Harem Years', through film and performance.

To argue that homes and the harem system, particularly in the context of Huda and Amina, as institutions of patriarchal power and control, are heterotopias for the secluded and the veiled female in Old Islamic Cairo.

And finally, to depict this by proposing a theatrical output that attempts to sympathize and spatialize multiple lived experiences (of Huda's onto Amina's), employing tactics of mirroring, of doubling, or of uncanny manifestations (haunting).

AMINA AND HUDA

NAGUIB MAHFOUZ'S 'PALACE WALK' & HUDA SHA'ARAWI'S 'HAREM YEARS: THE MEMOIRS OF AN EGYPTIAN FEMINIST'

Amina and Huda Sha'arawi

Palace Walk portrays Amina, the protagonist of Naguib Mahfouz’s novel who experiences extreme purdah at the hands of his tyrannical husband and consequently is secluded from the outside world. A doting and unquestioning character, the novel also highlights gender dynamics within the domestic and public/pedestrian realm and how Amina, secluded for more than 25 years, transforms her home into spaces of refuge. Palace Walk interestingly is set between 1917 -1919, significant years in Egypt’s history; the Egyptian National Revolution in which, in their respective capacities, men and women participated in the revolt against the British Occupation. This protest, which Huda Sha’arawi participated in and, yet Amina, observed, signified a progressive act which not only afforded women mobility, but women asserting themselves as political agents and activists, a domain previously heavily gendered. Huda Sha’arawi (Harem Years) represents (Palace Walk) Amina’s antithesis, whereby Huda advocated for the freeing and ultimate unveiling of the Islamic Woman then, Amina’s mobility was heavily restricted by Al-Sayyid Ahmad, at times under a distorted and self-serving understanding of religious duty (“A strict disciplinarian, the patriarch of the family bases his harsh regime on his understanding of the Qur’an… (Grace, 2004, p.80).

Huda’s memoirs map her childhood and adolescence, which she struggled and ultimately revolted against the restrictive expectations and limitations of being a wife, as she states “she felt [he] was limiting her unjustly [and grew depressed and restless] (at some instances of her childhood) (Sha'arawi, 1987, p.59). They also map her immersion into active feminism and advocacy for the Muslim women to be free. Huda separated from her husband for 7 years within months of marriage, upon learning that Ali Shara’awi has an extra-marital child, which Margot Badran states: “during these years [of separation] Huda Shara’awi gradually came to an awareness of the constraints imposed upon women in Egypt and devoted the rest of her life to the fight for women’s independence and the feminist cause.” She continues; “with her new-found freedom she took an increasingly militant stand in the harem and became engaged in Egypt’s nationalist struggle which culminated in independence in 1922.” (Sha'arawi, 1987, p.i)…

THE 'UNHOMELY FRAMEWORK'

BEHIND THE SCENES

THE SET: SCENE MAPPING & THE JAWWAD RESIDENCE

THE 'THEATRE'

As Naguib Mahfouz employs some historically accurate histories and landscapes in Islamic Cairene ‘Palace Walk’, mapping the story was possible. Naguib Mahfouz locates the home at the present day Amir-Beshtak Palace. A series of images (sourced from present day satellite imagery, historical archives and stills from the film) were also sourced and stitched together to provide somewhat a visual reference and/or understanding of Amina’s domestic and outdoor experience.

To provide a visual anchor for the film, a physical speculation of the Jawwad Residence (where Amina’s family resides) was proposed. The building design was influenced and guided by the remaining partial structure of the Amir-Beshtak Palace itself, the fictional depiction of the residence in both Bayn al-Qasaryn and Palace Walk, medieval principles of segregation (harem) in the residence and other Ottoman palace contemporaries/counterparts in Old Cairo, such as the Bayt al-Suhaimy and Bayt Mustafa Ja’afar.

AMINA'S HETEROTOPIAS: THE JAWWAD RESIDENCE

THE 'THEATRE'

According to Marsha Marotta in her article MotherSpace: Disciplining through the

Material and Discursive, she quotes Foucault in asserting ‘that the organization of space defines power relations in everyday life; that is social control and control over practices are achieved through the control of space’. (Marotta, 2005, pp.17-18). Beyond the material or territorial space that we inhabit, gender role performances in the homeplace are formed by their discursion (knowledge and instruction of how one conducts themselves in these spaces). As such, as Marotta infers, this determines an ‘ideologically appropriate individual’ who partakes in these ‘disciplinary practices’ (Marotta, 2005, p.19). This drawing indicates in the Jawwad Residence, Amina’s (and by extension, her daughters') spaces of ideal gender performance and occupation vis-a-viz spaces that are not ideal for her to inhabit, and refuge spaces she establishes. Each drawing foreshadowing the three acts in the film.

NEW FICTIONS

A SCRIPT

DOUBLED SITES

TRIPTYCH

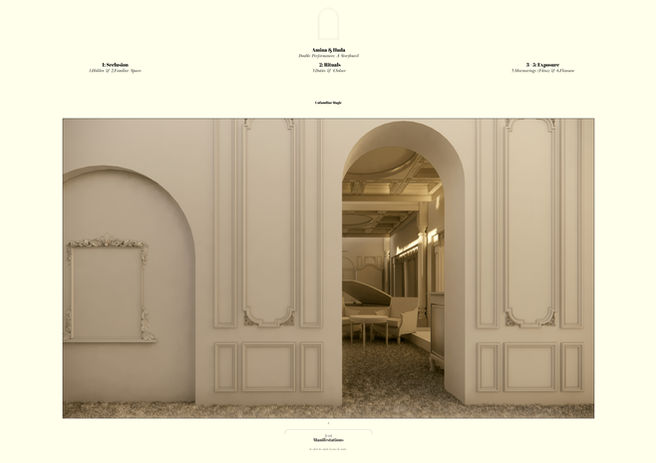

The following are a set of choreography layouts and sections that portray the insertion forms (Huda) (line drawings portrayed on the left) and the existing architecture portraying Amina’s home or rather the theatre set in its anomalous, doubled forms. Although materiality is a layer of interpreting the uncanny, the forms in this section are devoid of texture and or material to not only emphasize the spatial configurations that are proposed to produce the unheimlich, but also infers a ghostly, anemic or deathly characteristic, seemingly ‘familiar’ in form yet made strange.

1. UNFAMILIAR MAGIC

Unfamiliar Magic: which denotes the reversal of spaces that Amina and Huda particularly occupies. That is Huda as a newly-wed bride relinquishes her outdoor freedom (i.e playing in the courtyard) to settle to a married life of seclusion.

2. ACTS OF SERVICE & GUILTY PLEASURES

Acts of Service & Guilty Pleasures: which Amina serves her family breakfast (performs her wifely duties), and Huda is reprimanded from her pleasures (such as playing the piano) and reminded of her status as a wife.

3. FITNA

Fitna: which Amina makes her way to the oven room, and is interrupted by an altercation between Huda and Ali, which, as a result, Huda leaves…

EXPLAINERS

PARALLELS

1. UNFAMILIAR MAGIC

Explainer 1:

[i/m]: Unfamiliar Magic: Amina & Huda

Where Amina’s interior becomes Huda’s.

In Palace Walk, Naguib Mahfouz notes the roof and the oven room as spaces of refuge for Amina, our protagonist, under the panopticon that is her husband and the harem. Amina’s married life is one of seclusion and being limited to the interior. This condition, in Huda’s childhood, was incomprehensible. And yet her brother, young as her, as she played in the courtyard, her space of refuge, would jest to her: “a girl, [is] always outside while I, a boy, pass my time inside”. She responded, “Tomorrow it will be just the opposite”… (Sha'arawi, 1987, p.44). Tomorrow came; on her wedding day Huda acquiesces to being shown an eloquently appointed apartment, to which, for a moment, she was ‘won over by this magic’ (Sha'arawi, 1987, pp.55-56)

Amina encounters this ‘magical’ occurrence’ in her ‘own’ courtyard, where Huda ponders on the room she has been assigned, and the courtyard she once knew…

NB: In the film, Bayt Al-Qasaryn (1987), scenes that would depict Amina inhabit these spaces are unfortunately not included (the oven room with Umm Hanafi, the live-in worker, and the roof), two significant spaces that the author indicates, respectively, she feels most at home and sees the outside. In the film, only Aisha, her daughter, instead, is depicted with Umm Hanafi as they prepare breakfast.

2. ACTS OF SERVICE & GUILTY PLEASURES

Explainer 2:

[d/d]: Acts of Service & Guilty Pleasures: Amina & Huda

Where Amina performs her homemaking duties and Huda is reprimanded from doing otherwise.

Where a wish is rekindled, and a pastime is put out…

In her memoirs, Huda recounts her struggle to adapt to life in the harem and the mounting restrictions posed on her mobility and pleasures, such as playing the piano. As such Huda would have to come to terms with her role and duties and her coming of age as a female; however, she felt that she ‘was [being] limited unjustly’ (Sharaawi, 1987, p.59)

Apart from her wish to visit the Al-Hussein Mosque, Amina, seemingly, shows no inkling of resistance and abides to the command of the house and the patriarch. During breakfast, she witnesses a vision of Huda as she is reprimanded from playing the piano as the wall becomes transparent to expose a view of the Mosque…

The explainer aims to portray a seeming reversal of roles the women assume in the home. One is conditioned, through restrictions imposed, to assume the proper role of a good wife and to abandon or curb indulgences that may distract from performing these ‘acts of service’. The explainer also infers to how women are spatially regulated and relegated to being a wife, a female in the harem, where it is improper or haram (forbidden) to act out certain rituals, and where performing proper rituals/gender performances in designated spaces is a signifier of a good wife.

3. FITNA

Explainer 3:

[i/m]: Fitna: Amina & Huda

In which Amina contemplates a walk, and Huda takes one…

In Palace Walk, on the roof top, Amina would routinely ‘fix her eyes on the minaret of the mosque of al-Husayn’ (Mahfouz, 1990, p.35). Her ‘yearnings mingled with sorrow’ as she knew she would not be allowed to go (Mahfouz, 1990, p.35). As she quits her morning ritual and descends downstairs, prompted by an out of place, she proceeds to the main qa’a (reception) of the house where she witnesses an altercation between Huda and Ali; Huda is aware that Ali has a son out of their marriage, to which Huda leaves and separates from her husband. Intrigued, Amina proceeds to make her way to the courtyard, where all of these visions have begun.

The scene aims to capture desires, wishes and forms of resistance that both Amina and Huda wrestle with due to imposed purdah and the harem system; that is Amina witnessing a fellow woman leave and essentially resist these patriarchal spatial regulations juxtaposed with her earlier pondering of clandestinely and momentarily resisting similar circumstances.

AMINA & HUDA

FILM

أمينة وهدى